Aneurysm Segmentation

Introduction

The assessment of aneurysm rupture risk assists with pre-operative treatment planning and enables in-silico investigation of cerebral hemodynamics within and in the vicinity of aneurysms. However, ensuring precise and robust segmentation of cerebral vessels and aneurysms in neuroimaging modalities such as three-dimensional rotational angiography (3DRA) is challenging. The aneurysm constitutes a small proportion of the image volume, resulting in a large class imbalance (relative to surrounding brain tissue). Additionally, aneurysms and vessels have similar image/appearance characteristics, making it challenging to distinguish the aneurysm sac from the vessel lumen.

From left to right: 2D slice from a reconstructed 3DRA image; the maximum intensity projection (MIP) of the 3DRA image; and a 3D simulation-ready mesh of a cerebral aneurysm (blue) and the major vessels (white) in its vicinity reconstructed from its corresponding main vessel segmentation.

From left to right: 2D slice from a reconstructed 3DRA image; the maximum intensity projection (MIP) of the 3DRA image; and a 3D simulation-ready mesh of a cerebral aneurysm (blue) and the major vessels (white) in its vicinity reconstructed from its corresponding main vessel segmentation.

Result

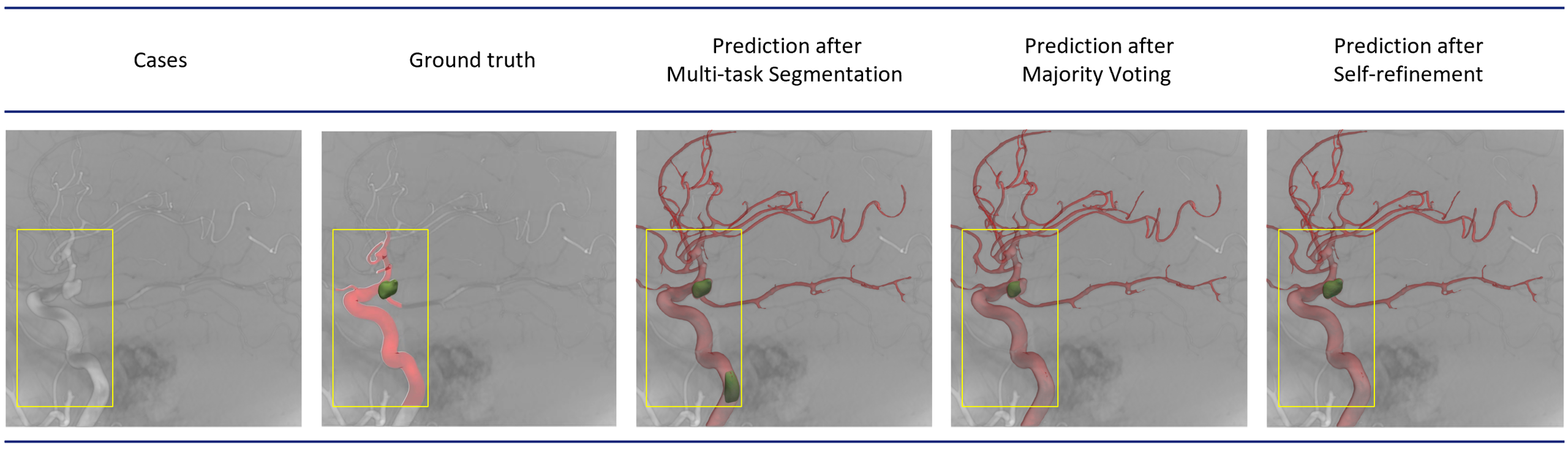

The surface meshes generated using the vessel and aneurysm segmentations predicted at different stages of our segmentation pipeline are shown in Fig. These figures demonstrate the utility of the proposed post-processing steps to suppress false-positive predictions for the aneurysm and refine the same. Cropped vessels share similarities in topology and appearance with aneurysms near patch boundaries. Therefore, initial segmentation using the proposed multi-class segmentation network (step 2 in Fig) is prone to incorrectly labeling tortuous vessels and vessels near patch boundaries as aneurysms (example in the third column of Fig). These false-positive predictions for aneurysms are artifacts of patch-based learning due to the limited spatial context available to the network during feature learning and can be effectively reduced using majority voting. The resulting aneurysm segmentation following the suppression of false positives by majority voting (see the fourth column of Fig) is used to provide aneurysm location and extract patches in the neighborhood, which are fed back into the multi-class network to refine the segmentation near the aneurysm (called’ self-refinement). The improvement in aneurysm segmentation accuracy afforded by these two post-processing steps involving majority voting and self-refinement is also highlighted for the test set in Fig.

3D renderings of obtained segmentations after different steps.

3D renderings of obtained segmentations after different steps.

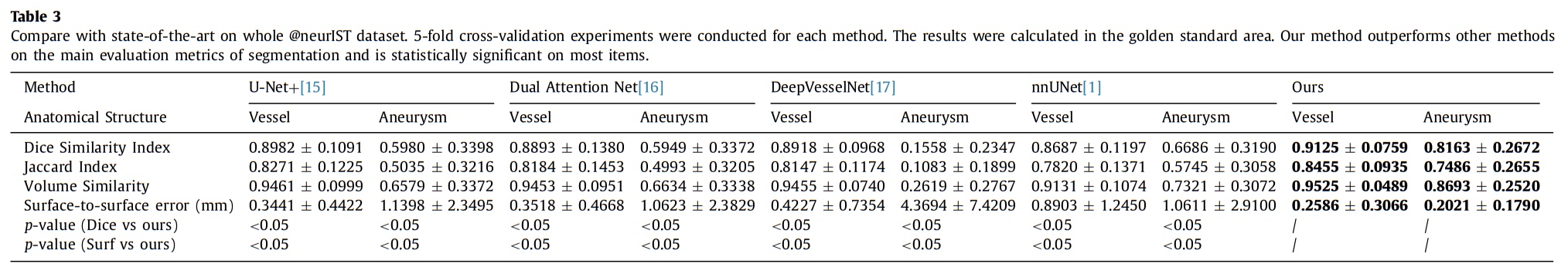

On the internal clinical dataset, our method consistently outperformed several state-of-the-art approaches for vessel and aneurysm segmentation, achieving an average Dice score of 0.81 (0.15 higher than nnUNet) and an average surface-to-surface error of 0.20 mm (less than the in-plane resolution (0.35 mm/pixel)) for aneurysm segmentation; and an average Dice score of 0.91 and average surface-to-surface error of 0.25 mm for vessel segmentation. In 223 cases of a clinical dataset, our method accurately segmented 190 aneurysm cases.

Conclusion

This work aims to alleviate class imbalance and inter-class interference, which are common and challenging problems in cerebrovascular and aneurysm segmentation. The deliberately designed network architectures such as the cascaded transformer, multi-view block, and wide block as well as the proposed post-processing strategies of the majority voting and self-refinement contribute positively to mining vascular and aneurysm features through the proposed end-to-end trainable network. The aforementioned issues are also present in brain MRA and CTA when it comes to cerebrovascular and aneurysm segmentation. The proposed model is generic and can be applied to mitigate the issues of class imbalance and inter-class interference in brain MRA and CTA, promising to facilitate accurate clinical analyses. The systematic evaluation of the model performance on other modalities would be the scope of future work.